By Joshua Lavender

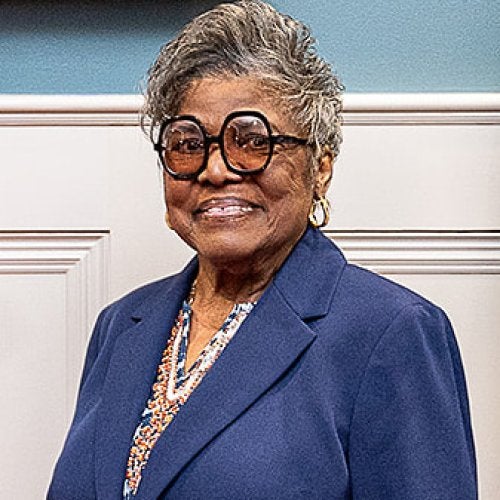

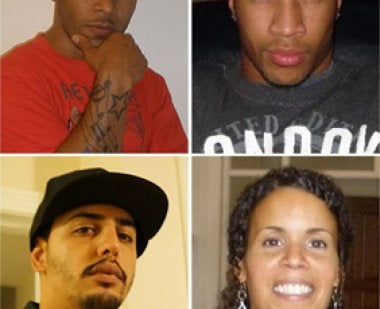

Pictured are Dr. Tara Brown and her PAR co-researchers: Jesus Santos, Edwin Alamo, and Newlyn De La Rosa.

The crippling effects of poor educational and socioeconomic conditions on young people who leave school before graduating are well documented. But discussions about these youths – colloquially called “dropouts” – tend to focus on their culpability, on their presumed unwillingness to persist in school and rise above their circumstances. Part of the problem may be that, despite all the research on the subject, the voices of these marginalized people are seldom or poorly heard. In this way, Dr. Tara Brown contends, how marginalization happens is itself obscured. An assistant professor in the college’s Education Policy and Leadership program, Dr. Brown practices a form of inquiry – participatory action research (PAR) – that purposefully seeks out and amplifies these voices.

Based on the work of education theorist Paulo Freire and grounded in the belief that authentic understandings of social problems require the knowledge of those directly affected by them, PAR is an empirical methodology in which researchers collaborate with representatives of the population they study. With the aid of three local co-researchers, Dr. Brown has recently conducted a mixed-methods study of young adults without a high school diploma living in a mid-sized, post-industrial American city with a majority Latina/o population. Drawing data from interviews with forty-three subjects and six service providers, as well as observational field notes and questionnaires from 220 subjects, this PAR study illuminates the systemic challenges these youths face in both educational and employment contexts.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are well over three million people between the ages of 18 and 24 who have left the education system without a high school diploma or GED. For these young adults – disproportionately Latina/o, African American, Native American, and low-income – economic prospects are bleak. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that upwards of 60% of them are unemployed, and most who are employed work low-wage, part-time, or temporary jobs with few opportunities for developing skills, earning a living wage, or starting a career. National economic factors contributing to their narrow prospects abound: increasing globalization, shifts from industrial to service economies, employers’ reliance on contingent labor, the weakening of unions and worker protections, and a mostly stagnant minimum wage. And these factors beget a variety of other problems: declining investment in social services, inadequate schools, and a rise in street crime. The hardest-hit areas tend to be smaller cities, where local economies formerly depended on manufacturing, and inner cities where low-skill workers are concentrated. Against this backdrop, Dr. Brown’s study reveals a debilitating structure of opportunity.

Predictably, the study’s participants felt that their troubles began with the low quality of education provided by their struggling school district, which had never met Adequate Yearly Progress benchmarks and was subsequently taken over by the state. Ninth grade was especially difficult: of the study’s forty-three interviewees, 17 had repeated the 9th grade at least once, and only one person in this subset went on to the 10th grade. The school context actually diminished their self-perceptions as learners: outside of school, participants described themselves as smart, quick learners, able to reach their goals, but in school, they saw themselves as slow learners, lazy and unfocused. They described their high school as a chaotic place where adults had little control and they felt distracted and unsafe. They also saw signs of street crime spilling into the school: students sold drugs, carried weapons, and settled disputes with violence. This environment posed high risks for academic failure, disciplinary exclusion, arrest, and incarceration.

More surprisingly, Dr. Brown asserts, these students’ lack of knowledge about policies and procedures and the school's obligation to students and families enabled school administrators to violate their educational rights. Many of the study participants reported being “counseled out” of school – told they had to leave because they were too old or had fallen too far behind. The majority did not realize they were entitled to public education until the age of 21 (or 22, in the case of special education students), and they had interpreted the dropout age of 16 not only as the age at which they could legally leave but also the age at which the school could terminate them for any reason. In many cases, school administrators deemed these students “over-age” at 17. Believing they had no recourse, these students accepted the situation and left.

Most interviewees with disciplinary troubles said they had not received suspension or expulsion hearings, which the school was legally obligated to conduct. None of the participants discharged for academic or disciplinary reasons when they were 16 or older reported receiving the school’s assistance in securing an educational placement elsewhere. Incredibly, this was even the case for special education students, for whom the school was obligated under federal law to provide this service. Of the 28 interviewees who left school of their own accord, only four did so formally; most simply stopped attending. A few said a caring teacher inquired into their whereabouts, but none recalled a phone call from an administrator or an official letter from the school. And while the vast majority of participants indeed blamed their own circumstances, attitudes, and behaviors for their failure to graduate, the data also strongly suggests that school staff did not effectively address participants' academic or social troubles and in some cases actually contributed to participants’ failure in school.

The study’s formal employment data suggests that, after leaving school, dropouts often experience their lack of a secondary credential as a “glass ceiling” that is extremely difficult to offset with job skills, experience, or a work history. For the participants, a confluence of barriers to employment – job scarcity, a large pool of low-skill job seekers, and inadequate transportation – produced a highly competitive job market in which they were badly positioned. Of the forty-three interviewees, 36 reported looking for work in the prior six months, but only 5 had a job in the formal economy. Nineteen had worked for a temp agency – where lack of a secondary degree was less of an obstacle, but employment was sporadic, unstable, and unpromising – and 24 said they had worked “under the table.” Twenty-three participants reported having engaged in illegal activities, most often to cope with joblessness and underemployment. Nineteen participants had been jailed and were burdened with a criminal record – an immutable barrier to employment and economic stability.

These people’s circumstances – hanging onto society’s edges – seem depressing, but where others may see only a hopeless decline, participatory action researchers see promise. Perhaps this is why Dr. Brown uses the pseudonym “Newhope” for the community in which she conducted her PAR study. Her research team is currently planning an educational rights summit for youth and families in the community, and a local organization has used the study’s data and findings to propose a charter school specifically designed to serve youth who have dropped out of high school. And here at the College of Education, Dr. Brown uses the study findings in her work with graduate students.

Another fundamental aspect of participatory action research is helping local co-researchers build their own capacity to transform their lives. In this respect, Dr. Brown’s PAR study is enormously successful. Three young men from the community were enlisted as co-researchers and trained in empirical research and research ethics. Their involvement brought crucial insights to the study, enhancing the relevance of data collection instruments and the authenticity of analysis. These co-researchers have presented the project with Dr. Brown at national research conferences, such as the one hosted by the American Educational Research Association (AERA), and are presently working with her on manuscripts for peer-reviewed publication. Two of the co-researchers, who had previously dropped out of high school, enrolled in college after joining the project, and one has recently secured a well-paying job in the tech industry after three years of unemployment.

In essence, Dr. Brown’s work challenges perceptions that dropouts are solely responsible for their own economic marginalization by showing how they are made vulnerable as workers. Their rates of joblessness, social service use, and lack of tax contributions, in addition to their implication in criminal activity, consistently frame them as “drains on the economy” in a rhetoric of culpability and threat. While this rhetoric may bring attention to the problem of dropouts, it also diminishes their humanity. Rather than being drains on society, Dr. Brown argues, they are individuals whose promise is being sapped by the educational and socioeconomic arrangements of the post-industrial economy.

Dr. Tara M. Brown is an assistant professor in the Minority and Urban Education specialization in the Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. Her research focuses on forms of school exclusion, such as disciplinary exclusion and dropout, among low-income adolescents and young adults in urban communities. She holds an Ed.D. from the Graduate School of Education at Harvard University.