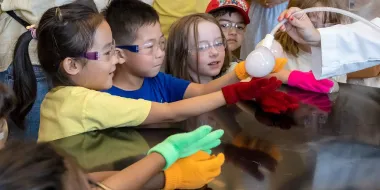

Students in protective glasses fidgeted beneath hanging glass beakers in a University of Maryland chemistry lab, awaiting a lesson on the states of matter with the attention span of 5-year-olds.

So for this group of preschoolers, Senior Lecturer Lenea Stocker Ph.D. ’13 skipped the Bunsen burners. She instead pulled out red, white and blue Legos—familiar to her audience and a perfect metaphor for the subject. After all, she pointed out, atoms are the building blocks of matter.

The field trip is one of dozens that the Center for Young Children (CYC), a pre-K and kindergarten program in the College of Education, takes its classes on each year across the University of Maryland campus. Celebrating its 75th anniversary this year, the CYC has long used labs and gardens and construction sites as an extension of its building just beyond the Denton Community (even if the 3- to 6-year-olds sometimes need a fruit pouch pick-me-up before they walk back).

“Hands-on experiences are essential for our program. The children can interact, question the experts, and draw conclusions,” said teacher Cecilia Fowler ’03. “On our way here, a child pointed to the bricks and told me, ‘That’s a liquid.’ I said, ‘Hmm, that’s interesting. Why do you think that?’ And now, on the way back, we’ll talk about it again.”

The CYC takes a “project” approach, in which its 90 children delve deeply into a particular topic for weeks or even months. It’s a research-based method of teaching that makes the curriculum accessible for learners of all levels, including children who are multilingual or have disabilities. That’s because the CYC is not only a school, but also a lab for UMD human development and early childhood investigators, as well as a demonstration site for College of Education students.

“What UMD students see when they come here is what research tells them reflects the way that children learn and become the most successful,” said CYC Director Jennifer Smallwood-Holmes.

That’s evident in how CYC teachers let students lead through project-based work, which is more active and engaging than traditional teaching methods, she said. For each topic, teachers find out what students already know (including misunderstandings), the types of experiences they’ve had and what they want to know, helping them make sense of the world around them.

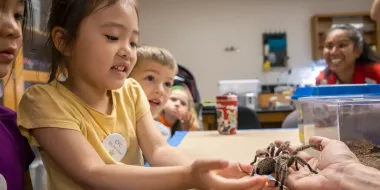

One morning at UMD’s Insect Zoo, kindergartener Sebastian Lucic had an urgent question: “Can you make him poop?” he asked entomology master’s student Eric Hartell as he offered up a millipede for Lucic and his classmates to pet.

“No, but his poop is very good for the soil,” Hartell said. Lucic thought about it, then announced he was naming the creature “Stripey.”

After a month-long study of insects, the children were eager to handle creepy-crawlies in the Plant Sciences Building. A leopard grasshopper, vividly red and yellow, was “tickly and sticky,” said one brave tot. Black Bess beetles, the size of a large paperclip, wandered from tiny hand to tiny hand. “He loves you, I think,” said Abigail Lynn to Nora Hurst.

With two previous trips to the woods and ponds near the CYC to find bugs on their own, the children didn’t need as much simplifying as Hartell had imagined, he said. They shouted out answers to the questions entomology Faculty Assistant Todd Waters asked, such as the number of legs insects have, what pollinators are and which animals eat bugs.

“We always think before we start a project, ‘Do we have resources we can tap into on campus?’” said teacher Amy Laakso ’09, M.Ed. ’17. “These are really enriching experiences that they remember.”

Last school year, she led her kindergarten class in two projects: bikes and scooters in the fall, visiting RecWell’s Bike Shop, and noodles in the spring, with classroom cooking lessons and a trip to Noodles and Company on Baltimore Avenue.

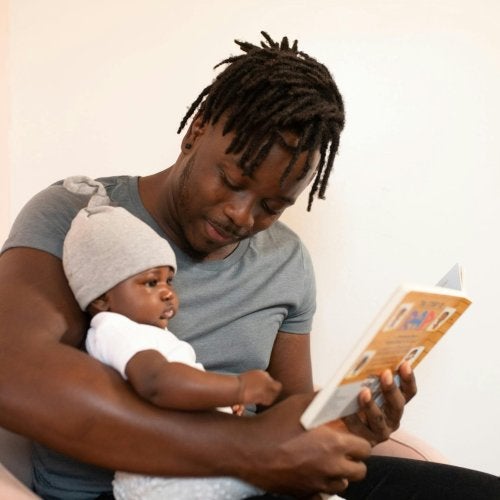

The micromobility study was a particular hit with Mark Wakefield’s 6-year-old daughter, Naomi, he said.

“She was actually learning to shift from a balance bike to a two-wheel bike,” said Wakefield, instrumental ensembles manager at the School of Music. “She came home and told me all the different parts that they learned about at the bike shop, and it just made her want to get out there.” By the end of the semester, Naomi was zooming independently on two wheels.

The experiences expand students’ worldviews beyond the lessons at hand. For example, seeing Stocker wear a lab coat and demonstrate “elephant toothpaste” pouring out of a giant beaker—when many of the children had been exposed to images only of male scientists—was eye-opening and prompted questions.

The natural curiosity that the curriculum sparks in the children is his favorite aspect of the CYC, said Wakefield. “To have them engaged and feeling ownership of their learning is the biggest thing.”