Influence of Perceived Cultural Barriers on Mental Health Help-seeking by Asian American Students

Asian immigrant parents’ perception of mental health and a lack of knowledge about mental health might create barriers for their children finding help for mental health issues in school-based settings in the United States, a College of Education study indicates.

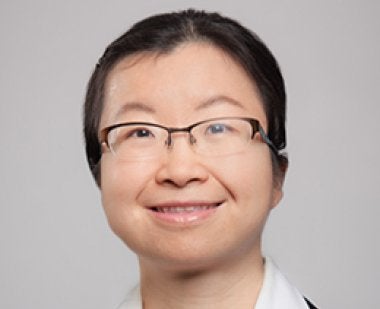

For instance, the parents surveyed had trouble identifying symptoms of bulimia, and nearly two thirds dismiss antidepressants as useful for treating depression, according to the study led by Cixin Wang, an assistant professor of school psychology. The findings suggest that a number of barriers, ranging from cultural issues to lack of resources, make it difficult for parents to secure school-based intervention for their children.

“There are many barriers preventing children and parents from seeking mental health services not only in the community but at school,” Dr. Wang says. “It can be language barriers, it can be stigma, and it can be lack of culturally competency, possibly, among providers that act as barriers.”

In the University of Maryland study, published in July in School Mental Health, the researchers used interviews and surveys to assess levels of mental health literacy (MHL) of Asian immigrant parents—MHL measures symptoms recognition and knowledge of appropriate treatment options related to various mental health issues. The researchers evaluated the MHL of Asian immigrant parents using case vignettes describing bulimia or depression, and by assessing the parents’ perception of barriers preventing adolescents from seeking help through school-based mental health services.

“Prior research has mainly focused on mental health services in hospitals [and] outpatient clinics, and less about school based mental health services, but youth are more likely to receive mental health services in schools rather than from other sectors,” says Dr. Wang, a school psychologist in the Department of Counseling, Higher Education, and Special Education.

The study included 19 Asian immigrant parents. The results revealed that only one-third of parents were able to identify bulimia, but that approximately three of four parents correctly identified depression. The majority of parents considered close friends, school counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, and general doctors helpful in treating adolescent mental health challenges, but less than half of the parents considered social workers or antidepressants helpful.

The researchers pinpointed a number of cultural barriers, including knowledge, attitudinal and structural and practical barriers, that might be at play in shaping Asian-American immigrant parents’ perception of mental health services in schools. For instance, unfamiliarity with the U.S. educational system might generate misperceptions about confidentiality of school-based mental health services, or parents might have a cultural preference for using an informal support system or come from a culture that does not discuss or stigmatizes mental health. Additionally, other practical issues, such as a lack of resources and providers, created barriers to accessing school-based mental health services.

The perceived lack of cultural competency and sensitivity among providers acts as another key—and less explored—barrier to adolescents seeking mental health services in schools, Dr. Wang says. In the study, Asian-American parents reported that some mental health providers maintained a Western mindset in judging strict parenting practices common in Asian cultures.

“For example, one mother mentioned that the counselor was shocked by some common parenting practices, and one girl, instead of getting help with her mental illness, started to defend her parents,” Dr. Wang says. “The provider, by doing that, created a barrier for treatment.”

The findings emphasize the need to improve school-based providers’ awareness of the hurdles that Asian parents and children face in seeking help for mental health. In particular, Dr. Wang says cultural competency should be an integral part of the preparation for teachers and other school-based staff.

“It is important to understand what Asian American parents perceive as barriers for Asian-American adolescents to seek school based mental health services,” Dr. Wang says. “If the schools and mental health practitioners don’t know the barrier exists, then they won’t be able to do anything to remove the barriers or make the help-seeking process easier.”

Recently, Dr. Wang was awarded a grant to develop a culturally-responsive parenting intervention for Asian-American adolescents struggling with mental health issues or bullying at school. In addition to teaching parenting strategies, the intervention also aims to help Asian immigrant parents learn about the U.S. school systems and the services provided at school, helping to specifically address some of the misconceptions and cultural barriers, Dr. Wang says.

Dr. Wang’s research interests include bullying prevention and mental health services in schools, especially among culturally and linguistically diverse students.