Can Parenting Blunt the Pandemic’s Blow to Kids?

Being a parent is hard in normal times— and being a kid is hardly a cinch. Add in a raging pandemic, and homebound bliss can be tough to find.

University of Maryland College of Education researchers are working to understand how stress related to COVID-19 affects the child-parent relationship and mental health, with early findings suggesting that pre-pandemic factors may predict child behavior difficulties during the pandemic —but that parental nurturing can help to overcome some of them.

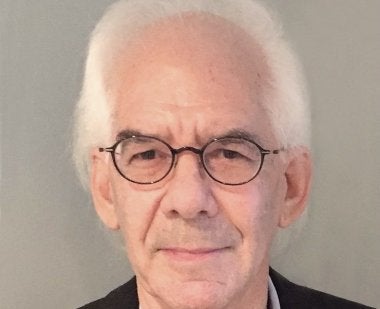

Led by Professor Kenneth Rubin of the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology, the Families and Children’s Experiences (FACE) of COVID-19 study has grown from a Maryland-focused project into a worldwide research collaboration. It includes study sites in Canada, China, France, India, Italy, Portugal, South Korea, Turkey, and elsewhere in the United States.

At each location, researchers are exploring how COVID-19 affects family functioning and lifestyle changes over time to determine factors that most help parents and children manage during the pandemic. They particularly want to know how outcomes vary from culture to culture, based on cultural values that can influence how parents and children behave and interact.

“Learning about the effects of COVID-19 between countries and cultures may lead to a better understanding of why some communities or cultures do better or worse under pandemic stress,” said Rubin, who has studied children’s social and emotional development, parenting, and child and parent mental health for more than 30 years and directs the Laboratory for the Study of Child and Family Relationships.

The research team recently completed recruiting 100 to 150 families with children ages 3.5 to 7 from each site. Parents responded to questionnaires related toCOVID-19 on six occasions over nine months. At the same time, parents provided information about their personal well-being, parenting practices, and children’s social and emotional development throughout the pandemic. The findings will evaluate how and whether pandemic-related stress changes household relationships and whether any factors are especially protective, such as parenting styles or access to medical and social support systems.

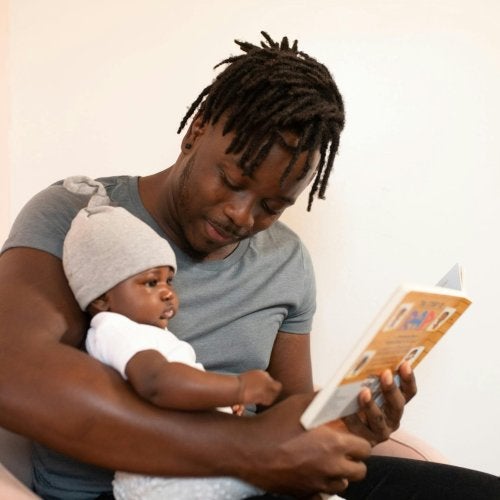

The Maryland portion of the study began soon after the start of the pandemic. Preliminary findings suggest that child irritability prior to COVID-19 predicts conduct problems during COVID-19, but also that irritable children with nurturing parents do not develop these behavior problems. Interestingly, during COVID-19, irritable children become less prosocial—which includes behaviors related to sharing, caring and helping—if their parents are less nurturant; however, pre-COVID-19 irritability did not predict declines in prosocial behavior in children with responsive and sensitive parents.

But parents need the necessary support and resources, including financial, to cope with pandemic-related stress and promote a healthy home environment, the study suggests.

Across study sites worldwide, the researchers expect to find considerable variability in whether families become stronger or more at odds after the pandemic. But Rubin said he’d make similar recommendations to parents now as he would if COVID-19 didn’t exist.

“Being sensitive, supportive, and kind no matter how you feel inside as a parent, is so incredibly important,” Rubin says. “I think parents have to take it upon themselves, regardless of age of the child, to have patience and be responsive and sensitive to the needs of their kids.”