Parental Involvement a “Protective Factor” for Mental Health

Middle schoolers who feel their parents are more involved in their education have fewer mental health problems resulting from being victims of bullying, including fewer suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and less overall difficulty with mental health, new research from the College of Education finds.

A lack of perceived parental involvement appears to have the opposite effect on students, resulting in more mental health issues and more suicidal thoughts and behaviors, according to the paper published this month in the journal School Psychology.

The research findings have particular resonance in an era of increasing adolescent suicide rates; according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, suicide rates have risen more than 30% in half of states since 1999. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young people, claiming the lives of more than 6,000 people ages 10 to 24 in 2016.

The middle school years can be challenging for students: Bullying becomes more prevalent, several mental health disorders have their onset during this period, and parents tend to become less involved in children’s education. The research, based on data collected from more than 300,000 Georgia students at 615 middle schools, suggests that parents who maintain involvement can play an important role in their adolescents’ mental health.

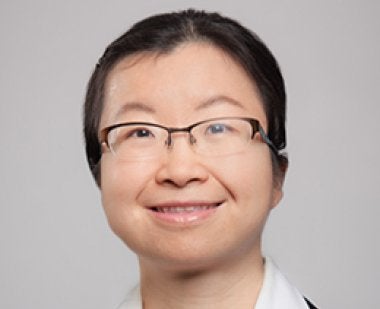

“Peer victimization has been linked to increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among youth, and we wanted to identify some protective factors,” said the lead author Cixin Wang, an assistant professor in the Department of Counseling, Higher Education, and Special Education. “At the school level as well as individual level, perceived parental involvement in education was related to fewer suicidal thoughts and behaviors, suggesting it is a protective factor.”

Previous studies have examined how parental involvement in education, ranging from help with homework to simply talking about school, helps children’s academic achievement. But less is known about whether parental involvement in education also benefits school children’s socio-emotional health.

Among the findings, parental involvement acted as a protective factor against only face-to-face bullying, not cyberbullying. Additionally, parental involvement was more protective for girls than boys and more so for eighth-grade students than sixth and seventh graders.

The researchers also compared the results for students from Asian, black, Latino and white backgrounds, expecting the buffering effect of parental involvement might be stronger for minority students. “But in general, we found that parental involvement was more beneficial for white students compared with ethnic minority students,” Wang said.

Overall, the research points to the critical need for parents to stay in tune with schoolchildren’s mental health, an issue not given enough attention in the past, she said. In addition, the need to prevent cyberbullying and reduce its negative impact on youth is key, but it is not yet fully understood, and may require additional research, Wang said.

Dr. Wang’s research interests include bullying prevention and mental health promotion in schools, especially among culturally and linguistically diverse students. In addition to studying victimization in middle schoolers, she also recently collaborated on an article, first authored by her doctorate student Kavita Atwal, on victimization and adjustment among Sikh American adolescents, and was featured in a prominent newsletter on bullying prevention in February. In addition, she recently received a $25,000 award from AT&T to develop and implement a bullying prevention program for cyberbullying.