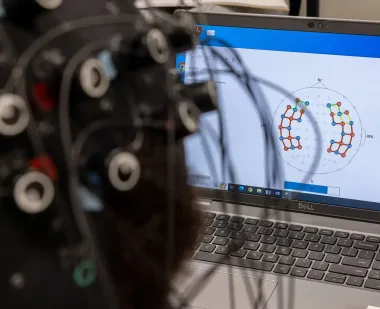

Rachel Romeo, a University of Maryland assistant professor of education, wants to shine a light on kids’ early development—literally. Using a technique called Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS), she beams light into the brain from sensors on a stretchy black cap, pinpointing blood flow to measure brain activity.

But in summer 2022, she realized she would have a hard time including a swath of the population in her study, because that light can’t easily penetrate Afro-textured hair, which is dark and densely curled. Yet her focus is on socioeconomic disparities in learning and development; she had to find a way to work with kids from all backgrounds.

“Most of the time in neuroscience research, if you can’t get a good signal from a participant, you just exclude them or you throw that data away,” said Romeo, who directs the Language, Experience, and Development (LEAD) Lab. “This contributes to underrepresentation.”

More than 70% of research participants in the U.S. are white, and as a white woman, Romeo didn’t know where to turn to learn how to change that dynamic. So she put out an ad for a lab assistant to help braid Black hair—and serendipitously, Abria Simmons ’25 had just declared a human development minor and enrolled in one of Romeo’s classes. She wasn’t a professional, but learned from generations of women in her family and was eager to help increase Black representation in neuroscience.

“There’s a lot of distrust in African American communities of medical research because of the neglect of African American bodies in earlier research studies, so it’s really important that they feel comfortable enough to be included today,” said Simmons, an aspiring counseling psychologist for kids and teens.

Now, she’s heading the effort to develop best practices for braiding and styling Afro-textured hair for fNIRS neuroimaging. She initially conducted a literature review but only found a few recommendations for EEG caps, which work differently than fNIRS. So she turned to Black barbers and hairstylists for tips, then started recruiting volunteers so she could experiment on their hair before the start of Romeo’s trials with 3- and 4-year-olds this fall.

“This has been a real friends and family project for me,” Simmons said. Throughout the summer, she brought five participants, including her brother and best friend. She first tried cornrows, which she’s most familiar with, braiding them in different patterns to avoid the optodes (sensors) on the cap.

By the end of the summer, she determined that the most successful braiding style involves creating a middle part, then braiding from the center of the scalp down toward the ears. With different curl and hair-growth patterns, however, it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution.

That’s why Romeo gave the go-ahead for Simmons to purchase a cart full of barbershop products, including clips and combs, tubs of edge control and gel, and a hair dryer and diffuser, so that people with dreadlocks or shorter hair also have options. It’s already proven useful: Romeo brought in her first 4-year-old Black participant, and since his hair wasn’t long enough to be braided, his mom used the gel to slick his hair up and out of the way.

Simmons knows how much effort it takes to care for and style Afro-textured hair, so she makes sure to schedule times in the lab based on participants’ wash days and prioritizes the health of the hair as she works. Some of her earliest memories involve three- to four-hour braiding sessions with her mom as she fell asleep in her lap as a toddler, with Disney princess movies playing in the background.

“It was definitely a bonding experience,” said Simmons, who took what she learned and combined it with YouTube tutorials to develop her own style as a teenager.

In September, she traveled to the Flux Society conference for developmental cognitive neuroscience with Romeo and other LEAD Lab members, where Simmons won best poster out of more than 130 presentations. Having tenured professors and longtime researchers seek her advice on data collection challenges was surprising but validating.

“There’s not many Black women in our research field, so I really want to represent my community,” Simmons said. She’s planning to expand on her poster presentation and write a paper next summer, and hopes her findings can give scientists the tools to conduct more equitable studies.

Romeo said, “I needed someone who was creative and willing to take the plunge with us. I'm just really grateful to have a partner who is willing to flip institutions on their head and figure out how to make neuroscience more inclusive.”

Top image: From left, Assistant Professor Rachel Romeo and Abria Simmons ’25 place a fNIRS neuroimaging cap on volunteer Cole Parker. Simmons is developing best practices for styling Afro-textured hair for research on children’s early development.

Photos by Stephanie S. Cordle