An Innovative Intervention to Help Asian American Families Cope with Racism and Related Mental Health Difficulties is funded by a Grand Challenges Individual Project Grant from the University of Maryland. This eight-session, culturally sensitive intervention helps Asian American families talk about racism, discrimination and associated mental health issues and learn positive parenting practices and youth coping strategies.

The intervention is one of 11 projects involving College of Education faculty that were funded by Grand Challenges Grants earlier this year. In all, the university awarded more than $30 million to 50 projects addressing pressing societal issues, including educational disparities, social injustice, climate change, global health and threats to democracy. The Grand Challenges Grants Program is the largest and most comprehensive program of its type in the university’s history.

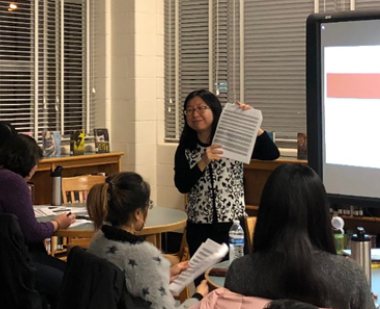

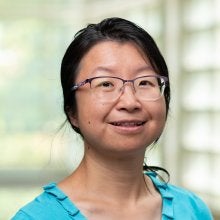

Cixin Wang, associate professor, is the principal investigator. Wang explains how racism affects the mental health and well-being of both Asian American parents and youth and how her intervention will help.

How do racism and mental health issues affect Asian American families?

In 2021, Pew Research Center found that 81% of Asian American adults felt that violence against them had increased in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. I co-authored a study in 2020 that found that half of Asian American parents and youth had experienced racism directly, and three-quarters had witnessed or heard about racism toward other Asian Americans. Both direct and vicarious experiences of racism are negatively related to mental health. Suicide has been the leading cause of death for Asian American youth ages 15 to 19 since 2016. Asian Americans are less likely to access mental health services than whites, possibly due to factors including low mental health literacy, stigma and lack of culturally competent providers.

Asian Americans experienced discrimination before COVID-19 (such as the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 and the internment of Japanese Americans in 1942). In addition, there are two pervasive master narratives about Asian Americans. The first is the perpetual foreigner stereotype, a racialized form of nativist xenophobia, where Asian American individuals are permanently seen as the “other” or “outsiders” in American society despite their U.S. citizenship. In our study, a very high percentage of Asian American middle and high school students experience being perceived as foreigners, even if they were born in the United States. Asian American history is also invisible in American history textbooks and public school curricula, reinforcing the perpetual foreigner master narrative.

The second is the model minority stereotype, which assumes that all Asian American students are high achieving or well adjusted. It was initially created to be used as a wedge against other minoritized groups, especially Black Americans, to simultaneously keep both groups quiet. When we interviewed Asian American high school students, some said peers say things to them like, “You’re Asian. You’re born to be good at math.” For these students who are good at math, this stereotype takes their pride in their hard work away from them. It also ignores the heterogeneity within the Asian American community and renders Asian American students who are struggling as “irrelevant and unworthy of attention.” Also, teachers might think Asian American students are doing fine and don’t need help, and this stereotype might prevent kids who are struggling at school (academically or social-emotionally) from getting the support they need.

How will this intervention make a difference?

Currently, there aren’t any interventions related to racism and mental health that focus on both Asian American parents and youth. In this intervention, we are working with 50 Asian American families with children ages 10 to 16. We will teach parents about positive communication skills, how to talk about emotions and racism in an empowering way, how to problem-solve with youth and how to work with schools to support youth. For the youth, we will use a social emotional learning curriculum adapted for Asian American youth. We will talk about how to navigate different cultures at home and at school and how to respond to racism, as well as coping and problem-solving strategies. We’ll collect data before the intervention and six months afterward to see if participants were able to use those skills and if they were helpful.

Why does this issue matter to you personally?

I’m Asian American myself, and my kids, my friends and I have experienced different types of racism during COVID. I hope that with our intervention, more Asian American families will feel comfortable talking about racism and youth mental health.