On a cool fall afternoon, graduate students sat on the floor of a classroom in the Benjamin Building, stitching together a quilt that reflected their visions of the world they wanted to live in.

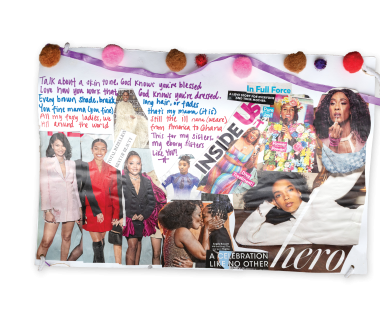

Led by Rossina Zamora Liu ’98, an assistant professor in the urban education specialization in the University of Maryland College of Education, the students had each created a “zine” expressing how they imagined building spaces of hope, healing and rest for themselves. The zines were brightly colored artworks fashioned from magazine cutouts, family photos, braided pipe cleaners and handmade paper suns and flowers. The students sewed their zines onto patches of burlap and then joined these together into a quilt that blazed with brilliant hues, rich textures and empowering words written with bold markers:

“We are not alone.”

“Rooted and reaching.”

“Black & Beautiful.”

“Safe. Seen. Celebrated.”

“This is no time for despair, but a time for resolve. We are authors of tomorrow’s democracy.”

“The zine-making process allowed us to express our feelings and share them in a space we created for ourselves,” said Colin McCarthy, a Ph.D. student specializing in urban education. “It was a labor of love, joining all of our individual thoughts, experiences and dreams together to create a representation of our community.”

Zines (pronounced “zeens”) first emerged in the 1930s as short magazines created by science fiction fans. They were adopted by the punk culture in the 1970s and then by the Riot Grrrl feminist movement in the 1990s in the form of self-published, photocopied pamphlets containing social commentary, personal stories, poetry, and collages and other artwork. These zines were created by and for the community, providing a space for people outside the dominant culture to express themselves.

In Liu’s graduate courses and community workshops, zines continue this legacy of amplifying untold stories in a grassroots, flexible format—but they take on even more open-ended forms. Zines allow a story to take any shape, without a predetermined structure or rules, Liu explained. The storytellers she has worked with have created zines in the form of collages, graphic novels, mobiles, origami and even wood carvings.

“A zine can be anything you want it to be,” said Liu. “You use the materials you have to capture your story that hasn’t been told or heard. Now you’re taking up space. You create this story, and people have to engage with it.”

Liu led her first storytelling workshop in the 2010s, at a shelter for unhoused individuals and families when she was a graduate student at the University of Iowa. In telling their stories, many of the writers started to create their own zines. Liu began the project with no funding, but she was amazed by the resourcefulness of the storytellers living in the shelter. They used found materials such as old planners, cardboard boxes and duct tape to make their creations, along with pens and paper that Liu’s department offered from their supply closet.

Since joining UMD as a faculty member in 2018, Liu has received four different internal grants totaling $95,000. With these resources, she can fund graduate assistantships and provide a variety of art supplies to the zine-makers, from glitter to ribbons to pom-poms, in addition to found and repurposed materials like fabric swatches, maps and old letters.

The zine-making process is “fluid and organic,” Liu said. She might begin by offering the storytellers an open-ended prompt, which she draws from the experiences and needs of the group.

“The storytellers are the experts. They’re the knowledge makers,” she explained. “The project evolves with them, just as their stories evolve.”

The zine-makers have explored themes connected to family history, personal experiences related to race and gender, a desire for home and a sense of belonging, and hopeful visions of the future. For example, in a recent installment of a zine-making workshop series, middle and high school students in Washington, D.C.’s Chinatown mapped out their visions of what they need in their schools and neighborhoods to feel safe and secure. Some of the students serve on youth councils that produce recommendations for community leaders; they told Liu that their zine-making work was helpful in informing their thinking about policies and advocacy.

Throughout the process, the zine-makers share their stories and experiences with one another as they feel comfortable, thereby building community. They also write artists’ statements about their work. Although zine-making is not a formal therapeutic practice, Liu said that it often leads to healing and transformation as storytellers feel heard and develop a deeper understanding of themselves.

“Any kind of storytelling is healing,” she said.

For Liu’s graduate students, zine-making has also proved to be a way to think about and enrich their own research. Although some students are uncomfortable with the lack of structure at first, they often find that zine-making leads their thinking in new directions–sometimes even to developing new conceptual frameworks for their research.

For others, like Satra D. Taylor, a Ph.D. student concentrating in higher education, zine-making is a welcome opportunity to integrate creativity and scholarship. Taylor considers herself a creative who enjoys writing poetry and producing visual art.

“I have not had many opportunities throughout my collegiate career that have enabled or encouraged me to intertwine my creative talents academically, especially in a way that supported my processing of emotions or sense-making that words could not capture,” said Taylor, whose zines have celebrated Black women’s beauty, boldness and joy. In her dissertation research, she is working with formerly incarcerated Black women to examine their access to and decisions about pursuing college studies in prison. She plans to incorporate zine-making in a focus group for the women to reflect on and share their stories.

Similarly, Huong Truong, a Ph.D. student concentrating in student affairs, has found that zine-making leads her to more innovative thinking. Her dissertation research centers on researching and telling the stories of Asian American communities, which will contribute to developing better practices and resources for college students. In one of Liu’s graduate courses, Truong created a zine using “blackout poetry”—blacking out words in a travel magazine’s exoticized depiction of a rural village in Southeast Asia and instead honoring ancestral knowledge and spiritual practices.

“Academia is restrictive in what is seen as formal, acceptable research,” she explained. “As a scholar, presenting my perspectives in a new form allows me to sit in the discomfort of broadening what research can encompass while being innovative in communicating my work. As a person who deeply values community, this process has given me space to connect with others by hearing and seeing their perspectives while sharing my own.”

Liu recently co-authored a study about zine-making in American Psychologist, along with her research team and several high school student zine-makers. The study focused on the zine-making processes of middle and high school students of color in Summer 2022. Liu’s team met with more than 70 students from three different communities, twice a week over four weeks. Each member of the research team created their own zine before the workshops began, to better understand the process so that they could more fully engage with the youth.

The students drew upon stories of their families, ancestors and communities as sources of strength as they explored their identities, processed experiences with racism and envisioned the future. The researchers concluded that zine-making can promote compassion and solidarity among people from different backgrounds, facilitate healing and help zine-makers understand who they are as individuals and in relationship with their families and communities.

For example, Vi Bao Le ’23, a member of the research team who was a psychology undergraduate student at UMD during the time of the workshops, created three-dimensional paper sculptures out of replicas of old family letters and writings.

“As a Vietnamese American woman and the daughter of refugees, understanding who I am is inherently intertwined with the stories of those who came before me,” said Le. “For my family, home has never been a constant, so creating my zine allowed me to explore: what does it mean to find home? For me, home is the culmination of the memories, stories, journeys, relationships, loss, joy and beauty of the simple things that we share.”

Rolonda L. Payne, who holds an Ed.D. in mathematics education from Morgan State University, is another member of the research team and a Ph.D. candidate specializing in urban education at UMD. She created her first zine as part of the project, celebrating the history of Black excellence in mathematics and exploring her childhood experiences of being the only Black girl in advanced math classes. She now integrates the practice of zine-making into her own work with youth.

“This approach not only stimulates creativity but also cultivates critical thinking skills as students navigate the overlap between personal narratives and broader societal contexts,” said Payne. “It accommodates various learning styles and enables students to engage with academic content in a more meaningful way. Through this exploration, the classroom transforms into a space of collective learning and empowerment.”

Liu plans to continue to follow the lead of the storytellers she works with as they explore their identities, communities and visions for the future through zines. This fall, for instance, Liu is working with high school students on creating self-portraits that reflect family stories and community solidarity. Many of the seniors are using the zine-making process to think through how they want to present themselves and their strengths in their college essays.

Beyond these workshops, Liu plans to keep sewing zines into quilts with her graduate students over the next several years, empowering them to share their stories and come together as a community. Eventually, she hopes to unite all of these zines into a single quilt.

“It’s a chance to dream and to say, ‘There is space for me, and I’m going to take it up.’ And I want this quilt to be obnoxiously big!” she said. “We need to continue humanizing each other and recognizing our whole personhood.”

Photos by Mike Morgan