When Jeni Stepanek first showed up for Paula Beckman and Sandra Newcomb’s support group for families of children with disabilities, they weren’t sure how they would help her.

It was 1989, and Stepanek had recently lost two children within eight months of each other. She had a new baby, was facing devastating hospital bills, and had paused her doctoral program in psychology in the midst of all that pressure.

Though doctors had attributed her older children’s health problems to a rare, recessive condition unlikely to be inherited again, her third child, Jamie, was born with challenges similar to her first two babies.

Those cumulative challenges led her to Project Assist, the support group, and a long-time relationship with the UMD College of Education. Project Assist provided in-home visits and parent support groups to Maryland families of children age 3 and younger with disabilities.

“Families are often dealing with the grief of having a child with disability. It was not the expected child,” said Dr. Newcomb, who retired as an assistant research professor in 2018. “They’re dealing with medical issues and getting the right services. When you have a kid with a disability, you may not have as much as common with another parent, and they might distance themselves.”

As the mother of multiple children with life-threatening disabilities, Dr. Stepanek (Ph.D. ‘08) was often confronted by stigma from the medical community and broader society.

“Soon after joining the support group, I realized I was pregnant with my fourth child, and was being judged by everybody – except Project Assist,” she said.

When the 12-week group ended, Drs. Newcomb and Beckman recruited Dr. Stepanek, due to her experience and psychology training, as a peer support provider. Eventually, she earned a special education doctoral degree at COE and became a faculty member.

A Medical Mystery, Explained

Like his siblings, Dr. Stepanek’s youngest child was born without control of his autonomic system.

Before Mattie’s arrival, Katie, blonde and cheerful, had lived to be almost 2. Stevie, a red-head, died at six months. Prior to his death at age 4, Jamie spent two years in a semi-comatose state with cortical blindness – the result of a cardiac arrest at age 2.

“My children came into the world clearly unwell, but it was not clear why they were unwell,” she said.

An avid runner at the time, an astute doctor noticed that Dr. Stepanek’s eyelids were drooping and she was easily winded. She was diagnosed with a rare mitochondrial disorder resulting from a 94% enzyme deletion that led to an adult neuromuscular disorder. Subsequently, her children were diagnosed with a 96% deletion, resulting in infant-onset of a rare form of neuromuscular disease.

“Our family history goes back to the 1700 and 1800s with predominant child death, but it would be called summer sickness, crib death, SIDS,” Dr. Stepanek said. “And then a woman will grow up, become an adult, become disabled as an adult and give birth to children who die.”

The diagnosis provided an explanation for her children’s medical fragility, but not a cure.

Teaching Mattie, Teaching Others

When Mattie was a toddler, a tracheotomy and a tumor resulted in a severe speech impediment. By teaching him to enunciate, his mother also inadvertently taught him how to read.

A gifted student from a young age, Mattie benefited from accompanying his mother to the university, where he was embraced and enjoyed making coffee for faculty.

“He liked to say he was three credits behind me,” Dr. Stepanek said. “He was born into a world where his mom was a teacher, a psychologist, and was now pursuing another doctoral degree. He didn’t stand a chance to sit around.”

Dr. Beckman, a professor in the Dept. of Counseling, Higher Education and Special Education, still remembers taking Mattie to the university bookstore to buy a Beanie Baby. The 5-year-old insisted on young adult science fiction instead.

“He picked it up and read, ‘It was a time of uncertain peace in the Galaxy,’” she said.

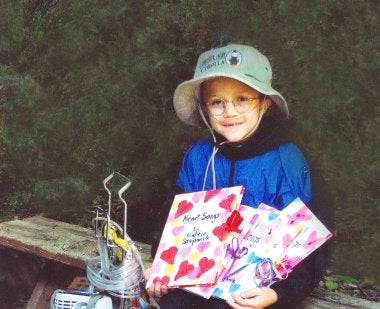

By then, Mattie had been writing for three years, since Jamie’s death. His poetry and short stories focused on peace and spirituality.

“Mattie benefited medically because he was the youngest, and he benefited emotionally because he learned from loving his brother who could not love back,” Dr. Stepanek said. “He learned to love someone simply because they existed.”

Mattie had three wishes when his health began to significantly decline at age 10: He wanted to publish a book, talk peace with President Jimmy Carter and have Oprah share his message.

When President Carter called, he was so moved by their conversation that he began mentoring the boy. Oprah invited him on an early September, 2001 show, but due to health concerns, it was rescheduled. Then, 9/11 happened.

“When Mattie, who is tiny in body but powerful in message, appeared on the show in October 2001, we had an audience desperate for peace,” Dr. Stepanek said. “He commanded attention just by speaking.”

Despite being famous for his prescient spirituality, he was also a funny and spirited boy, once giggling and hiding from a CNN camera crew interviewing him inside the Benjamin Building, Dr. Beckman recalled.

Mattie published seven books of Heartsongs and Just Peace poetry and essays, all of which became New York Times bestsellers.

When Mattie died at 13, President Carter gave the eulogy, calling him “the most extraordinary person whom I have ever known.” Oprah also spoke, and crowds closed the streets near the funeral.

The Mattie J.T. Stepanek Foundation continues his work by creating resources that promote peace for people of all ages. His legacy lives on at schools like the Katherine Thomas School in Rockville, Md., which serves students with disabilities, and an annual peace day.

Dr. Stepanek said she is grateful, even in her continued grief for her children.

“Tough things happen, but by choice I live with hope and purpose; that is not about being in denial,” said Dr. Stepanek, who has a pixie cut and a smile that alights her face. “I see the world as a good place with good people, and I am blessed with resilience, and purpose.”

Firsthand Understanding

Dr. Stepanek’s experiences as a parent of children with disabilities, a special education specialist, and a person with disabilities who relies on a ventilator and wheelchair, also inform her work as a technical assistance specialist.

Cancer treatments in her 50s combined with progression of neuromuscular disease resulted in significant vision and hearing loss. The changes gave her new empathy for the families she supports through COE’s Connections Beyond Sight and Sound, the Maryland and DC Deafblind Project, as well as for her own children’s hearing and vision challenges.

“I knew what it was like as a provider; I had respect for my children. But until I experienced vision and hearing loss, I had no idea what kids went through,” she said. “I have incidental knowledge that comes from being sighted and hearing for 50-odd years. I am blown away with amazement for how these children – who lost hearing and vision during their earliest years – are learning and socializing and communicating.”

Though she provides training and assessment, Dr. Stepanek is no longer able to go to clients’ homes due to mobility issues. But her experience with disability and as a mother to children with life-threatening complications helps foster a deep sense of trust with the families she supports.

“I am drawn to families that are judged. I want to say, ‘You are making good choices. Your child is worth our time and resources,” she said. “I was told my child wasn’t worth quality education. We need to continue to change attitudes, awareness and beliefs.”

She aims to help children with severe disabilities connect and learn according to individual potential. Drs. Newcomb and Beckman said Dr. Stepanek has given them new insights across decades of working together.

“Her experience as a parent dealing with the medical system, and then later as a person with disabilities, becomes a whole different way of looking at the world,” Dr. Newcomb said. “She has an amazing ability to be persistent and creative, both in parenting her children with disability but also living her life as an adult with a disability.”

For Virtual Peace Days 2020 & more info: mattieonline.com

Photos courtesy Jeni Stepanek

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of Endeavors, the UMD College of Education's alumni magazine.